Cyberattacks on local governments are speeding up, and the damage isn’t hypothetical: in Q1–Q3 2025 alone, government entities across the U.S. experienced 276 ransomware attacks, with over 443,000 records confirmed breached. Local agencies—including utilities, emergency services, and municipal governments—are increasingly seen as prime targets: critical enough to trigger fast ransomware payments, yet often still running on vulnerable legacy systems operated by overextended IT teams.

Threats are growing in volume and sophistication. AI is accelerating faster than any previous technology cycle, giving bad actors new ways to scale attacks and pushing the threat landscape forward at a pace few teams can match. Yet, while local governments know they are at risk, Springbrook’s two-year look at cyber readiness reveals a dangerous disconnect between awareness, action, and infrastructure.

Modernization is happening—but not evenly. Some organizations are advancing with stronger policies, improved tools, and more mature security practices. Others are still constrained by aging technology, staffing shortages, and budget tradeoffs that leave serious vulnerabilities unresolved.

These realities are reflected throughout the 2026 Springbrook Cybersecurity Report, a two-year overview of cyber readiness based on insights from 350+ respondents across IT, finance, and administration. The findings reinforce a critical truth: local governments aren’t ignoring cybersecurity—but awareness alone isn’t translating into resilience. And right now, that gap is where risk takes hold.

Awareness vs. Action

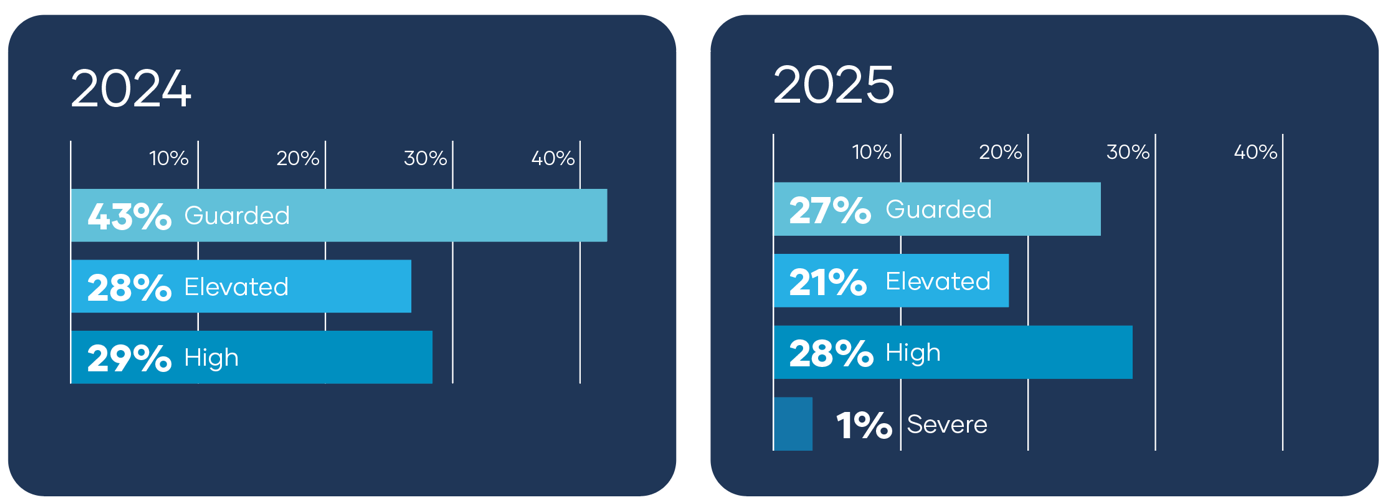

Local governments aren’t asleep at the wheel. Most organizations know the threat is real—and many continue to rate their cyber risk as Elevated or High.

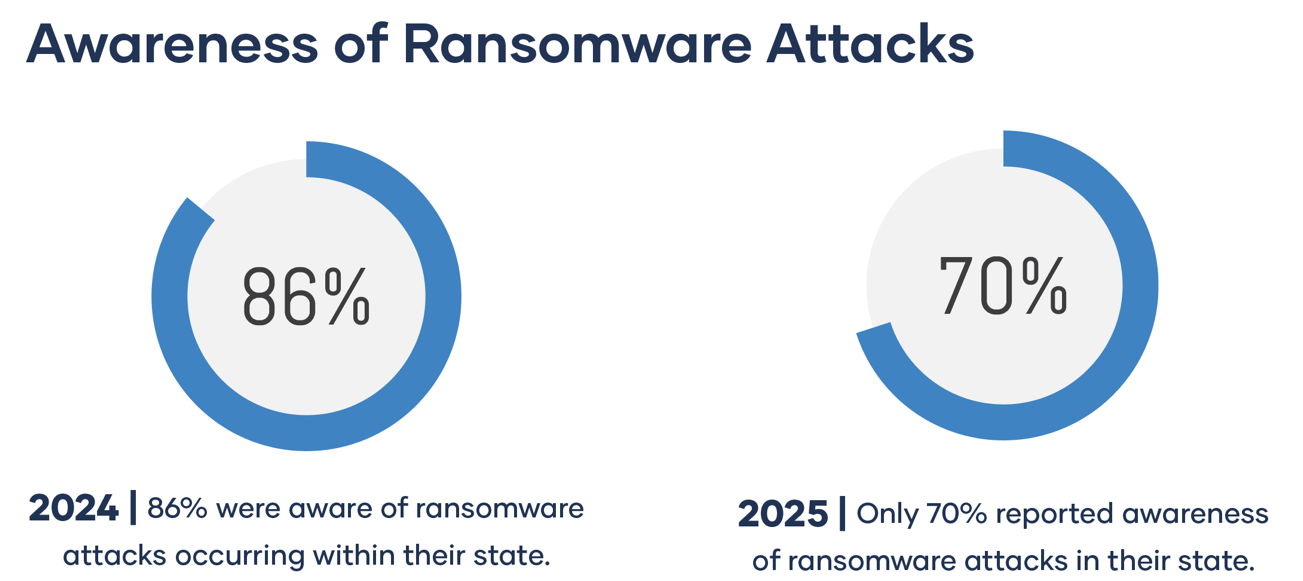

But recognizing the risk isn’t the same as staying engaged with it. In 2025, only 70% of respondents said they were aware of specific ransomware incidents in their state, down from 86% in 2024. That drop doesn’t mean ransomware is fading. It means the opposite may be happening: attacks are becoming so frequent that individual incidents are becoming easier to tune out.

In many organizations, ransomware is no longer viewed as an urgent outlier. It’s become operational noise—another headline, another breach update, another warning that registers briefly before getting pushed aside by the daily demands of serving residents, keeping systems online, and meeting budget requirements. When that happens, the threat loses the urgency needed to drive meaningful change. Over time, this creates risk normalization. And that’s where the most dangerous gap forms—not in awareness, but in follow-through.

Because knowing that attacks are happening isn’t the same as preparing for them. Resilience requires action: consistent patching, verified backups, segmented networks, incident response planning, ongoing training, vendor oversight, and the leadership support to prioritize cybersecurity even when resources are tight. Without such active preparation, ransomware doesn’t need to outsmart an organization—it only needs to outpace it.

Budgets are rising, but not keeping up with threats.

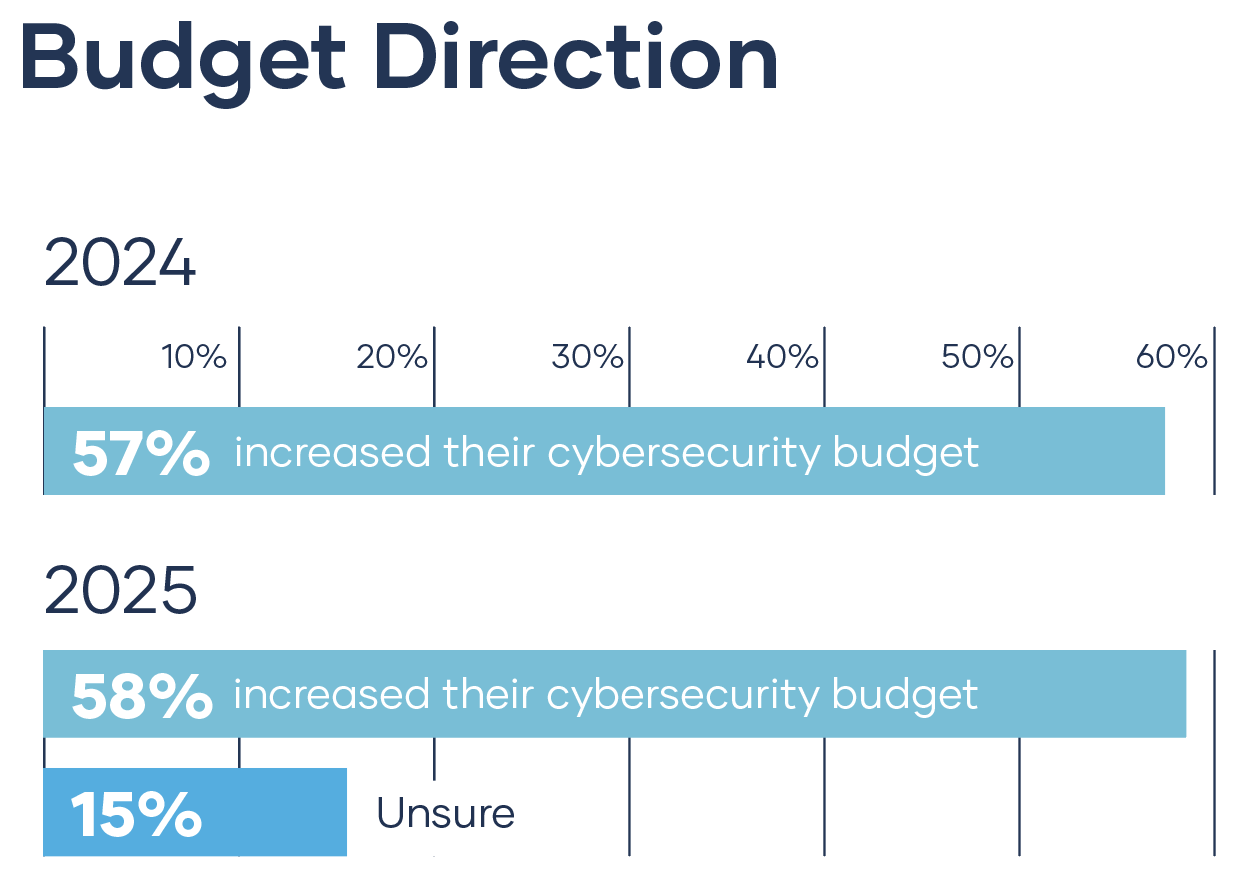

Even when local governments do prioritize cybersecurity, translating that urgency into sustained investment is another challenge entirely. The data shows that about 58% of organizations increased their cybersecurity budgets—and that number held steady across 2024 and 2025. But steady doesn’t mean sufficient. With national growth slowing, many agencies are making incremental gains while the threat landscape keeps accelerating.

That imbalance matters, because today’s cyber risk doesn’t scale gradually. It scales exponentially—especially as attackers adopt automation and AI-driven tactics that make campaigns cheaper, faster, and harder to stop. In that environment, modest year-over-year budget increases may help maintain the status quo, but they rarely create the kind of step-change needed to close foundational gaps.

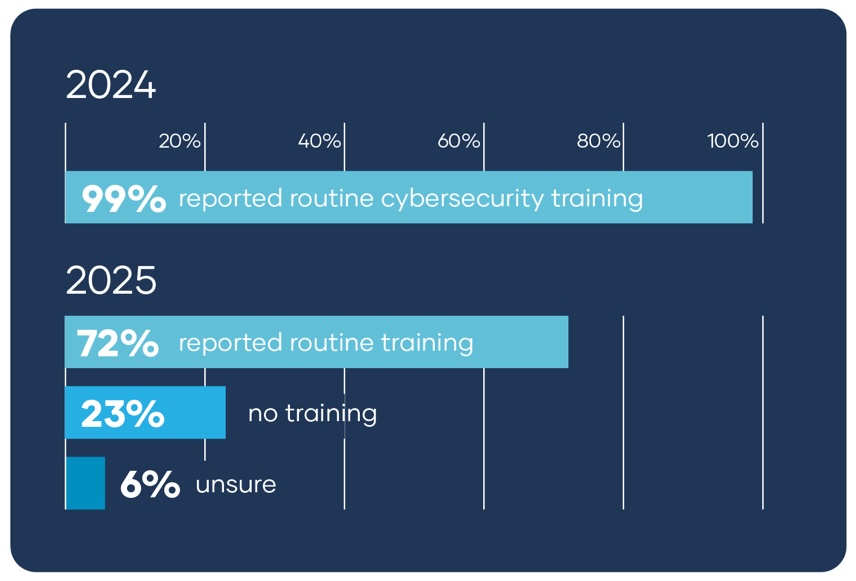

One of the clearest signs of this strain shows up in training. While in 2024 nearly all organizations previously described training as routine (99%), that number fell sharply to 72% by 2025, a major drop in one of the most practical and cost-effective defenses local governments have. Additionally, “training” doesn’t mean the same thing everywhere. In some organizations, it reflects consistent programs, simulations, and reinforcement. In others, it may mean a one-time module, an annual requirement, or informal reminders that are easy to deprioritize when workloads spike.

The result is uneven cyber hygiene—especially across smaller agencies where staff wear multiple hats and capacity is limited—creating predictable weak points, from gaps in incident response readiness to employees left without the repetition needed to recognize and respond to common threats.

Ultimately, the challenge isn’t that local governments aren’t spending. It’s that the spending often isn’t transformational. It’s incremental. And incremental improvements can’t keep pace with adversaries who are scaling faster, adapting faster, and exploiting gaps faster than budgets—and people—can respond

The hidden risk multiplier of fragmented ERP environments

Cybersecurity discussions often focus on threats, training, and budgets—but one of the biggest drivers of risk is less visible: the architecture underneath everything. When local governments are running critical financial and operational workflows across multiple disconnected systems, security doesn’t just get harder—it gets fragmented too.

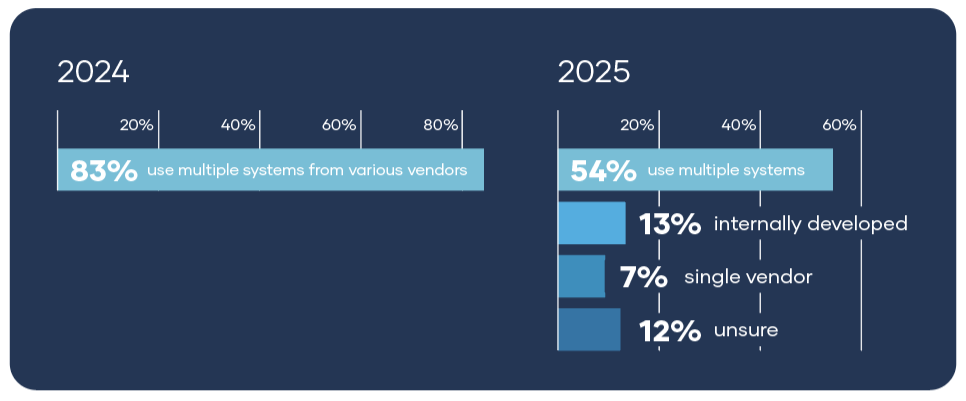

The good news is that some consolidation is happening. In 2025, 54% of organizations still reported using multiple systems, but that’s down from 83% in 2024, signaling real progress toward modernization. Still, the report highlights a red flag that’s easy to miss: a high volume of “don’t know” responses. And that matters, because uncertainty isn’t neutral in cybersecurity—it’s a visibility gap. It can mean teams don’t have a clear view of where data lives, how systems connect, who has access, or what controls exist across platforms.

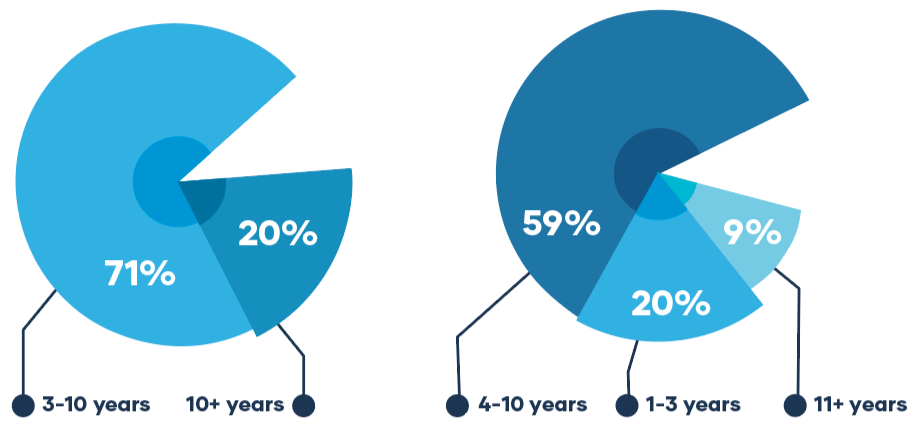

At the same time, legacy systems remain dominant and are often 3–10+ years old. That’s not just an IT detail—it’s a security risk. Older platforms can limit integration, complicate patching, and create “workaround culture,” where manual processes and exceptions pile up over time. The result is an environment that becomes harder to secure consistently, even with the best intentions.

This is where fragmentation becomes a risk multiplier, increasing:

- Identity complexity: Multiple applications often mean inconsistent permissions, duplicate accounts, and access that’s harder to audit—or revoke quickly.

- Patch gaps: Different systems = different patch cycles, different vendors, and different upgrade constraints, making it easier for vulnerabilities to linger.

- Incident response time: The more environments organizations manage, the more logs IT teams need to chase, the more endpoints they need to isolate, and the longer it takes to understand what happened.

- Vendor accountability issues: When security spans multiple platforms, responsibility can get blurred—especially during an incident when speed and clarity matter most.

And this is the core insight local governments can’t afford to overlook: cybersecurity posture is inseparable from technology architecture. Organizations can invest in better tools, stronger policies, and more training—but if the underlying environment is fragmented, security will always be harder to enforce, harder to measure, and harder to improve. Modernization isn’t just about efficiency. It’s about reducing exposure—by building an environment that’s easier to manage, easier to secure, and faster to recover when something goes wrong.

Foundational practices are still not universal.

Fragmentation isn’t the only multiplier. The 2026 Springbrook Cybersecurity Report points to a clear and concerning trend: foundational best practices—baseline protections—still aren’t universal. Not the “cutting-edge” defenses. Not the expensive, specialized tools. The fundamentals that help reduce exposure, limit damage, and make incidents easier to contain.

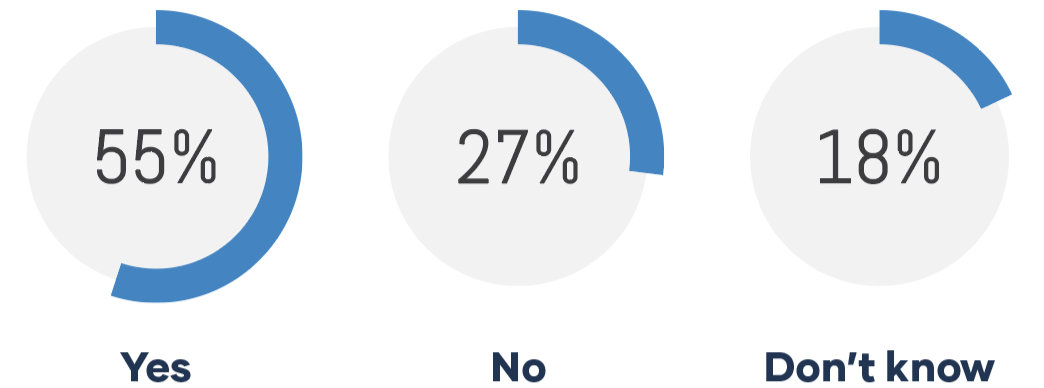

One example is Zero Trust. Nearly half of the organizations surveyed either don’t have a Zero Trust policy in place—or aren’t sure if they do. That uncertainty matters. Zero Trust isn’t a buzzword anymore—it’s a practical framework for limiting access, reducing credential-based risk, and preventing a single compromised account from turning into a full-scale incident. But without clear policy direction, Zero Trust remains an aspiration instead of an operating standard.

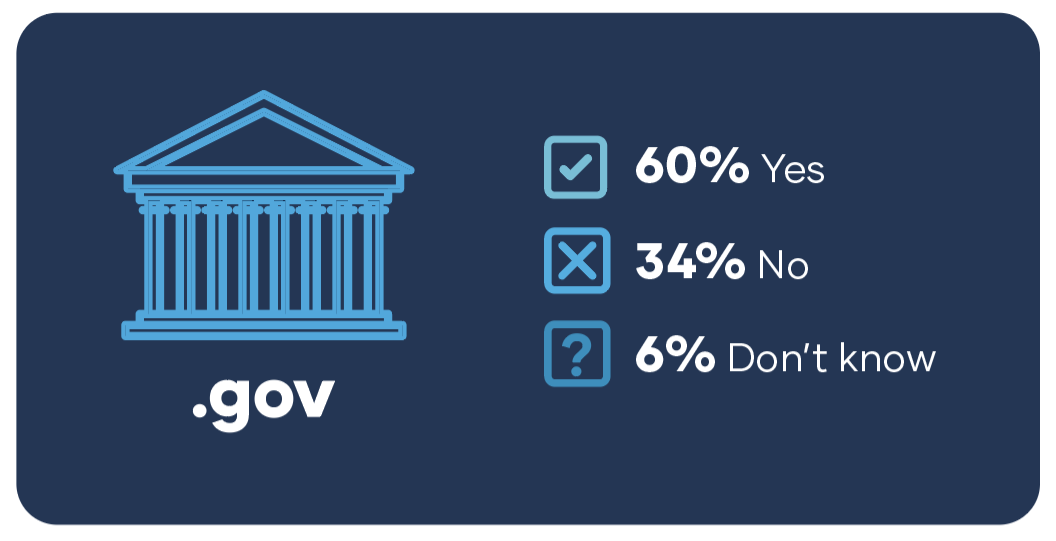

Another foundational signal is .gov domain adoption. About 40% of respondents say they either don’t have a .gov domain or aren’t sure. That may seem like a small detail, but it’s not. A .gov domain helps establish legitimacy and reduce confusion for residents, partners, and vendors—and it can play a meaningful role in reducing impersonation and phishing risk, especially as AI makes it easier to generate convincing fraudulent messages at scale.

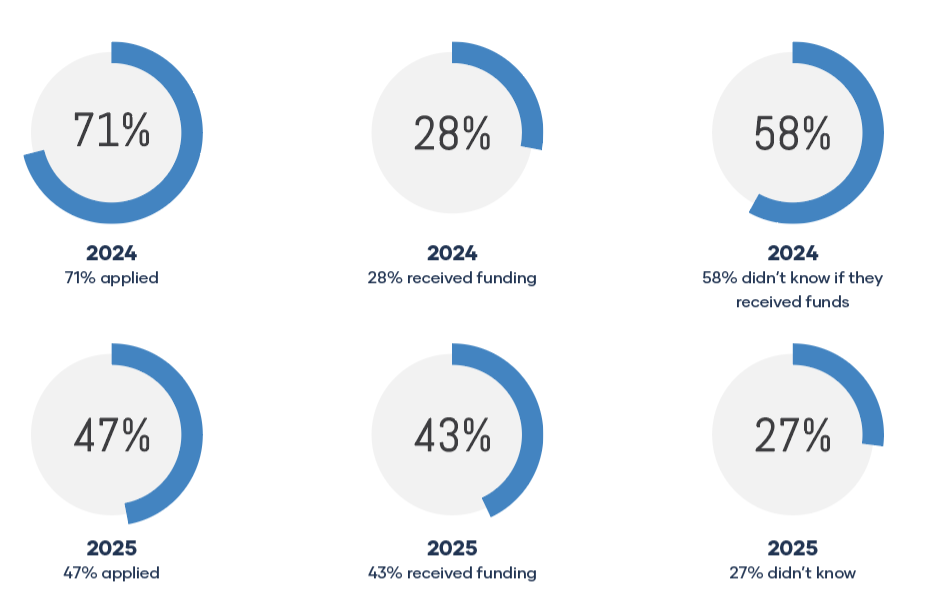

And then there’s the question of resourcing. Grant utilization has improved, but it remains uneven—and often underpowered compared to the scale of increasing cybersecurity threats. Many agencies still face the same barriers: limited staff time to pursue funding, complicated application requirements, and difficulty turning grant dollars into sustained capability once the funding window closes.

When such baseline protections aren’t consistently in place, it becomes almost impossible to build resilience. Because in cybersecurity, it’s rarely the most sophisticated failure that causes the biggest disruption—it’s the missing fundamentals that attackers can count on.

What the two-year trend tells us

When we analyze local government cybersecurity through a two-year lens, the story isn’t one of inaction—it’s one of uneven momentum. Progress is real. Intent is clear. But the data shows that many organizations are still caught between knowing what needs to change and having the capacity to make it stick.

Across the last two years, four takeaways stand out:

1) Awareness is high—but inconsistent.

Local governments understand they’re at risk, and many rate their environment as elevated or high risk. But awareness of specific incidents is slipping, and that matters. When real-world ransomware stories start to fade into the background, urgency can erode—and risk normalization can take hold.

2) Modernization is happening—but incomplete.

Systems are consolidating and modernization is underway, but fragmentation and legacy environments remain common. And when organizations lack full visibility into how systems, access, and data flows connect, security becomes harder to standardize, measure, and enforce.

3) Budgets are increasing—but modestly.

More agencies are investing in cybersecurity, but spending increases remain incremental. National growth is slowing, and the threat landscape is accelerating. The result is a widening gap where organizations are trying to meet modern threats with small, year-over-year adjustments.

4) Best practices are still not universal.

Some of the most important defenses aren’t advanced—they’re foundational. Yet many organizations still lack clarity or consistency around baseline protections like Zero Trust, .gov adoption, and fully resourced security programs. These gaps aren’t theoretical—they shape exposure every day.

The bottom line: local government is moving in the right direction. But the biggest risk isn’t a lack of awareness or intent—it’s the gap between intent and execution. And in a threat environment defined by speed, automation, and constant pressure, that gap is exactly where disruption takes hold.

What agencies can do in the next 12 months

The good news is that meaningful cybersecurity progress doesn’t always require a massive overhaul—it requires focus. Over the next 12 months, local government agencies can reduce risk quickly by prioritizing actions that simplify environments, strengthen access controls, and build repeatable discipline across teams.

Here are five moves that create real momentum—without waiting for “perfect” conditions.

1) Consolidate fragmented systems

Every additional system adds complexity: more logins, more vendors, more patch cycles, more blind spots. Consolidation reduces exposure by shrinking the attack surface and creating a cleaner environment for consistent security controls, auditing, and incident response.

2) Accelerate true SaaS adoption

Modernization isn’t just moving to “the cloud”—it’s adopting platforms built for continuous updates, stronger resiliency, and improved security by design. True SaaS solutions help agencies reduce the burden of patching, simplify management, and move away from environments where upgrades are delayed until risk piles up.

3) Prioritize identity and access control

If attackers can take over an account, they don’t need to “hack” anything else. Strengthening identity should be a frontline priority: tightening permissions, enforcing MFA, reviewing privileged access, and building clearer role-based controls. Identity is where a large share of incidents begin—and where they can often be stopped fastest.

4) Move training beyond annual checkboxes

Annual training alone isn’t enough in a threat landscape that changes weekly. The goal isn’t completion—it’s readiness. Agencies can improve outcomes by shifting to shorter, more frequent training touchpoints, practical simulations, and role-based reinforcement that helps staff recognize threats before they become incidents.

5) Treat grants as a cyclical strategy

Grant funding can be a powerful accelerator—but only if it’s planned like a cycle, not treated as a one-time win. Agencies that build repeatable processes for identifying opportunities, applying, and operationalizing funded initiatives are more likely to turn grants into sustained capability instead of short-lived projects.

The next year is an opportunity to reduce complexity, increase control, and strengthen the foundations that resilience depends on. Small moves—executed consistently—can change the risk curve faster than most agencies expect.

Cyber readiness is an operational priority, not just an IT challenge.

Cybersecurity in local government is no longer just a technical issue—it’s an operational priority tied directly to public safety, service continuity, and community trust. When systems go down, it’s not only data that’s at risk. It’s payroll, utility billing, emergency response coordination, and the everyday services residents depend on.

And the cost of inaction isn’t limited to a breach notification—it’s disruption. Missed deadlines. Delayed services. Lost confidence. Recovery efforts that pull time and resources away from the work that matters most.

Real resilience doesn’t come from awareness alone. It comes from integrated systems and sustained organizational support—the kind that turns cybersecurity from a reactive scramble into a built-in state of preparedness.